Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Passover and the Festival of Matzot: Synthesizing Two Holidays

Passover Beyond the Seder Night?

Soon, many of us will sit down with family and friends at our Passover seder and, in one fashion or another, recount the story of the exodus from Egypt. We will recall that the festival of Passover commemorates the night that God killed the first born in Egypt, avoiding the Israelite houses whose lintels and doorposts were smeared with the blood of a sacrificial lamb. We will note that instead of sacrificing a lamb each year on this occasion, as the Torah commands, we tell the story, using symbolic foods such as matzah and bitter herbs to help us remember both our ancestors’ experience and the sacrifice that we no longer perform. And then, the seder done and the dishes washed, the festival day (or two outside of Israel) over, we continue a six day period of restraining from all leavened products, chametz.

For many, the transition between the pageantry of the seder and the slow grind of the next six days is jarring. We “get” the seder; the ritual is so heavily overdetermined in words, food, and ritual that we can hardly not get it. The next six days, though, which largely replace active rituals with avoidance – well, what exactly are they about?

While not everybody will experience the disjuncture between the first day(s) and the next six, it is one that is already deeply embedded in the Torah itself. The holiday that today we call Passover had its origins as two separate holidays, Passover proper and the Festival of Unleavened Bread, chag ha-matzot.

The Torah itself is aware of this and attempts in various passages, some more successful than others, to reconcile them. Other passages focus on only one of these festivals. Exodus 12:1-14, for example is entirely about the single-day commemoration of Passover, before abruptly switching in verse 15 to the seven-day Festival of Unleavened Bread. According to Leviticus 23:5-6:

ויקרא כג:ה בַּחֹדֶשׁ הָרִאשׁוֹן בְּאַרְבָּעָה עָשָׂר לַחֹדֶשׁ בֵּין הָעַרְבָּיִם פֶּסַח לַי־הוָה. כג:ו וּבַחֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר יוֹם לַחֹדֶשׁ הַזֶּה חַג הַמַּצּוֹת לַי־הוָה שִׁבְעַת יָמִים מַצּוֹת תֹּאכֵלוּ.

Lev 23:5 In the first month, on the fourteenth day of the month, at twilight there shall be a Passover offering to YHWH, 23:6 and on the fifteenth day of that month the Lord’s Feast of Unleavened Bread. You shall eat unleavened bread for seven days.

One day of Passover followed by seven of unleavened bread? While the mepharshim (commentators) clearly assume that this means, as taken today, that one is to avoid chametz for a total of seven days (indeed, they barely comment on this verse), the text on its own implies the existence of two separate holidays.

Deuteronomy 16:1-8 contains one of the more complex attempts to reconcile these two festivals:

דברים טז:א שָׁמוֹר֙ אֶת חֹ֣דֶשׁ הָאָבִ֔יב וְעָשִׂ֣יתָ פֶּ֔סַח לַי־הוָ֖ה אֱלֹהֶ֑יךָ כִּ֞י בְּחֹ֣דֶשׁ הָֽאָבִ֗יב הוֹצִ֙יאֲךָ֜ יְ־הוָ֧ה אֱלֹהֶ֛יךָ מִמִּצְרַ֖יִם לָֽיְלָה׃ טז:ב וְזָבַ֥חְתָּ פֶּ֛סַח לַי־הוָ֥ה אֱלֹהֶ֖יךָ צֹ֣אן וּבָקָ֑ר בַּמָּקוֹם֙ אֲשֶׁר יִבְחַ֣ר יְ־הוָ֔ה לְשַׁכֵּ֥ן שְׁמ֖וֹ שָֽׁם׃

Deut 16:1 Observe the month of Abib and offer a passover sacrifice to YHWH your God, for it was in the month of Abib, at night, that YHWH your God freed you from Egypt. 16:2 You shall slaughter the passover sacrifice for YHWH your God, from the flock and the herd, in the place where YHWH will choose to establish His name.

טז:ג לֹא תֹאכַ֤ל עָלָיו֙ חָמֵ֔ץ שִׁבְעַ֥ת יָמִ֛ים תֹּֽאכַל עָלָ֥יו מַצּ֖וֹת לֶ֣חֶם עֹ֑נִי כִּ֣י בְחִפָּז֗וֹן יָצָ֙אתָ֙ מֵאֶ֣רֶץ מִצְרַ֔יִם לְמַ֣עַן תִּזְכֹּר֔ אֶת י֤וֹם צֵֽאתְךָ֙ מֵאֶ֣רֶץ מִצְרַ֔יִם כֹּ֖ל יְמֵ֥י חַיֶּֽיךָ׃ טז:ד וְלֹֽא יֵרָאֶ֙ה לְךָ֥ שְׂאֹ֛ר בְּכָל גְּבֻלְךָ֖ שִׁבְעַ֣ת יָמִ֑ים וְלֹא יָלִ֣ין מִן הַבָּשָׂ֗ר אֲשֶׁ֙ר תִּזְבַּ֥ח בָּעֶ֛רֶב בַּיּ֥וֹם הָרִאשׁ֖וֹן לַבֹּֽקֶר׃

16:3 You shall not eat anything leavened with it; for seven days thereafter you shall eat unleavened bread, bread of distress – for you departed from the land of Egypt hurriedly – so that you may remember the day of your departure from the land of Egypt so long as you live. 16:4 For seven days no leaven shall be found with you in all your territory, and none of the flesh of what you slaughter on the evening of the first day shall be left until morning.

טז:ה לֹ֥א תוּכַ֖ל לִזְבֹּ֣חַ אֶת הַפָּ֑סַח בְּאַחַ֣ד שְׁעָרֶ֔יךָ אֲשֶׁר יְ־הוָ֥ה אֱלֹהֶ֖יךָ נֹתֵ֥ן לָֽךְ׃ טז:ו כִּ֠י אִֽם אֶל הַמָּק֞וֹם אֲשֶׁר יִבְחַ֙ר יְ־הוָ֤ה אֱלֹהֶ֙יךָ֙ לְשַׁכֵּ֣ן שְׁמ֔וֹ שָׁ֛ם תִּזְבַּ֥ח אֶת הַפֶּ֖סַח בָּעָ֑רֶב כְּב֣וֹא הַשֶּׁ֔מֶשׁ מוֹעֵ֖ד צֵֽאתְךָ֥ מִמִּצְרָֽיִם׃ טז:ז וּבִשַּׁלְתָּ֙ וְאָ֣כַלְתָּ֔ בַּמָּק֕וֹם אֲשֶׁ֥ר יִבְחַ֛ר יְ־הוָ֥ה אֱלֹהֶ֖יךָ בּ֑וֹ וּפָנִ֣יתָ בַבֹּ֔קֶר וְהָלַכְתָּ֖ לְאֹהָלֶֽיךָ׃

16:5 You are not permitted to slaughter the passover sacrifice in any of the settlements that YHWH your God is giving you; 16:6 but at the place where YHWH your God will choose to establish His name, there alone shall you slaughter the passover sacrifice, in the evening, at sundown, the time of day when you departed Egypt. 16:7 You shall cook and eat it at the place that YHWH your God will choose; and in the morning you may start back on your journey home.

טז:ח שֵׁ֥שֶׁת יָמִ֖ים תֹּאכַ֣ל מַצּ֑וֹת וּבַיּ֣וֹם הַשְּׁבִיעִ֗י עֲצֶ֙רֶת֙ לַי־הוָ֣ה אֱלֹהֶ֔יךָ לֹ֥א תַעֲשֶׂ֖ה מְלָאכָֽה׃

16:8 After eating unleavened bread six days, you shall hold a solemn gathering for YHWH your God on the seventh day: you shall do no work.[1]

Deuteronomy has spliced the Festival of Unleavened Bread in verses 3-4 and 8 (indicated by indented text) into a coherent narrative of the sacrifice of the Paschal lamb.[2] (As biblical scholars have long noted, this passage also attempts to centralize in Jerusalem a ritual that had routinely been performe/d in the “settlements.”) The two festivals – or maybe even three, depending on how one counts the seventh day – have been molded into one.

A somewhat better but still messy attempt at reconciliation of the two festivals can be seen in Ezekiel 45:21-25. According to v. 21,

יחזקאל מה:כא בָּ֠רִאשׁוֹן בְּאַרְבָּעָ֙ה עָשָׂ֥ר יוֹם֙ לַחֹ֔דֶשׁ יִהְיֶ֥ה לָכֶ֖ם הַפָּ֑סַח חָ֕ג שְׁבֻע֣וֹת יָמִ֔ים מַצּ֖וֹת יֵאָכֵֽל׃

Ezek 45:21 On the fourteenth day of the first month you shall have the passover sacrifice; and during a festival of seven days unleavened bread shall be eaten.

The Hebrew is even more awkward than this translation, which adds the word “and” (not indicated in the Hebrew) to connect the two observances. By Ezekiel’s time (early sixth-century BCE) the two festivals were combined, but uneasily.

The Historical Preference for Passover

There is some limited evidence in the Tanach and elsewhere that just as more Jews today are attracted to Passover than they are to the observances the rest of the week, so too ancient Israelites thought Passover a more important holiday than the Festival of Unleavened Bread. After entering the Land of Israel under Joshua and undergoing circumcision (Joshua 5:10-11),

יהושע ה:י וַיַּחֲנ֥וּ בְנֵֽי יִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל בַּגִּלְגָּ֑ל וַיַּעֲשׂ֣וּ אֶת הַפֶּ֡סַח בְּאַרְבָּעָה֩ עָשָׂ֙ר י֥וֹם לַחֹ֛דֶשׁ בָּעֶ֖רֶב בְּעַֽרְב֥וֹת יְרִיחֽוֹ׃ ה:יא וַיֹּ֙אכְל֜וּ מֵעֲב֥וּר הָאָ֛רֶץ מִמָּֽחֳרַ֥ת הַפֶּ֖סַח מַצּ֣וֹת וְקָל֑וּי בְּעֶ֖צֶם הַיּ֥וֹם הַזֶּֽה׃

Josh 5:10 The Israelites offered the passover sacrifice on the fourteenth day of the month, toward evening. 5:11 On the day after the passover offering, on that very day, they ate of the produce of the country, unleavened bread and parched grain.

The passover sacrifice and its echoes of history are relatively clear. What follows, however, isn’t. The day after the passover offering they ate unleavened bread and parched (or roasted, kaluy) grain. There is no sign that they ate matzah with the passover sacrifice itself. Nor is a seven day festival mentioned here. It is possible that the eating of the matzah and grain were noted not as being done in fulfillment of a ritual, but as an agriculturally based celebration of entering the Land of Israel. And it is not entirely clear even that eating the matzah and grain were meant to fulfill ritual requirements.

King Josiah reinstitutes the passover sacrifice:

מלכים ב כג:כב כִּ֣י לֹ֤א נַֽעֲשָׂה֙ כַּפֶּ֣סַח הַזֶּ֔ה מִימֵי֙ הַשֹּׁ֣פְטִ֔ים אֲשֶׁ֥ר שָׁפְט֖וּ אֶת־יִשְׂרָאֵ֑ל וְכֹ֗ל יְמֵ֛י מַלְכֵ֥י יִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל וּמַלְכֵ֥י יְהוּדָֽה׃

2 Kgs 23:22 For the Passover had not been offered in that manner in the days of the chieftains who ruled Israel, or during the days of the kings of Israel and the kings of Judah.

The lack of mention of the Festival of Unleavened Bread seems even odder here, as it was the discovery of a scroll of Deuteronomy that supposedly precipitated the reinstatement, and Deuteronomy had already combined the holidays. About three centuries later, in 419 BCE, a letter (called by scholars “the Passover Letter”) was sent from Jerusalem to a Judean garrison in Elephantine, Egypt that appears to instruct its recipients on how to observe the Feast of the Unleavened Bread. The text of the letter reads:

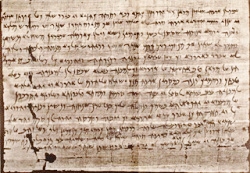

[To] my [brethren Yedo]niah and his colleagues the [J]ewish gar[rison], your brother Hanan[iah]. The welfare of my brothers may God [seek at all times]. Now, this year, the fifth year of King Darius, word was sent from the king to Arsa[mes saying,“Authorise a festival of unleavened bread for the Jew]ish [garrison].” So do you count fou[rteen days of the month of Nisan and] obs[erve the passover], and from the 15th to the 21st day of [Nisan observe the festival of unleavened bread]. Be (ritually) clean and take heed. [Do n]o work [on the 15th or the 21st day, no]r drink [beer, nor eat] anything [in] which the[re is] leaven [from the 14th at] sundown until the 21st of Nis[an. For seven days it shall not be seen among you. Do not br]ing it into your dwellings but seal (it) up between these date[s. By order of King Darius. To] my brethren Yedoniah and the Jewish garrison, your brother Hanani[ah].[3]

One wonders if this was news to the recipients.

It is clear that the biblical Passover, at least as understood in several texts, was seen as closely associated with the historical foundational event of the exodus from Egypt. The meaning of the Festival of Unleavened Bread, though, is more obscure, especially since it is not directly associated with the Pesach story. I agree with the scholars who posit that it likely originated as an agricultural festival, much like Sukkot and Shavuot. It is explicitly connected to spring, and Joshua 5:11 suggests a connection to agriculture. In this reading, it is a holiday focused on nature rather than history.

Understanding the Disentangled Holidays

Disentangling the festivals of Passover and Unleavened Bread has no halakhic implications. It does, though, attune us to the different dimensions of our current, combined holiday. This might best be seen at the extremes of Jewish practice. Traditional haggadot privilege the historical dimension of Passover; we barely find spring and agriculture in it. On the other hand, many haggadot developed by kibbutzim make Passover far more about nature than history.

We should not have to choose. The incremental but clear slide from late antiquity to the twentieth century in Jewish thought and ritual away from nature and towards history has, since the beginning modern Zionism edged back, just a little and in some circles, toward nature. There is no necessary reason, though, that nature and history need to be in conflict. The Passover seder need not be just about remembering the Exodus, but can also be a recognition of the wonder of spring and God’s work in creation. And if during the next six days we focus a bit more on enjoying our time off or outdoors, we can also remember our ancestors setting off into the desert, away from slavery and toward Sinai. This synthesis is the genius of Passover, and it is one that we should strive to embrace.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 6, 2014

|

Last Updated

December 26, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Michael L. Satlow is Professor of Judaic Studies and Religious Studies at Brown University. He holds a Ph.D. from JTS, is the author of Creating Judaism: History, Tradition, Practice and How the Bible Became Holy and the editor of Judaism and the Economy: A Sourcebook. He maintains a blog at mlsatlow.com.

Essays on Related Topics: