Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Molekh: The Sacrifice of Babies

An exhibit in the Sant’Antioco archaeological museum (Sardinia) reconstructs the layers of Sulci’s Punic “tophet,” with offering bowls to hold the baby’s bodies and dedicatory stelae. The Phoenician settlement of Sulci was part of the Carthaginian sphere of influence from the 8th century B.C.E. until its conquest by Rome in the 1st century B.C.E., when child sacrifice was prohibited. Photo: Daniel Ventura, Wikipedia.

Deuteronomy forbids following the Canaanite practice of “passing a child through fire”:[1]

דברים יח:ט כִּי אַתָּה בָּא אֶל הָאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר יְ־הוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ נֹתֵן לָךְ לֹא תִלְמַד לַעֲשׂוֹת כְּתוֹעֲבֹת הַגּוֹיִם הָהֵם. יח:י לֹא יִמָּצֵא בְךָ מַעֲבִיר בְּנוֹ וּבִתּוֹ בָּאֵשׁ...

Deut 18:9 When you come into the land that YHWH your God is about to give you, you shall not learn to do like the abhorrent things of these nations. 18:10 There shall not be found among you one who “passes his son or his daughter through a fire”…[2]

Rashi (R. Solomon Yitzhaki, ca. 1040–ca. 1105) explains that it was only a mock child sacrifice:

רש"י דברים יח:י ...עושה מדורת אש מכאן ומכאן ומעבירו בין שתיהם.

Rashi Deut 18:10 …One makes a fire on two sides and passes [the child] between them.

Moshe Weinfeld, among other scholars, also understand the ritual as one in which the child is symbolically burned but not actually killed.[3] In contrast, R. Moses Nahmanides (Ramban, ca. 1195–ca. 1070) understands it as child sacrifice:

רמב"ן ויקרא יח:כא ...היא נתינתו באש, שתמשול בו האור, לא העברה בעלמא...

Nahmanides Lev 18:21 …This refers to placing him in a fire, so that the fire overwhelms him, not just passing through…

Deuteronomy’s earlier reference to what seems to be the same practice supports the position of Nahmanides:

דברים יב:כט כִּי יַכְרִית יְ־הוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ אֶת הַגּוֹיִם אֲשֶׁר אַתָּה בָא שָׁמָּה לָרֶשֶׁת אוֹתָם מִפָּנֶיךָ... יב:ל ...וּפֶן תִּדְרֹשׁ לֵאלֹהֵיהֶם לֵאמֹר אֵיכָה יַעַבְדוּ הַגּוֹיִם הָאֵלֶּה אֶת אֱלֹהֵיהֶם וְאֶעֱשֶׂה כֵּן גַּם אָנִי. יב:לא לֹא תַעֲשֶׂה כֵן לַי־הוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ כִּי כָּל תּוֹעֲבַת יְ־הוָה אֲשֶׁר שָׂנֵא עָשׂוּ לֵאלֹהֵיהֶם כִּי גַם אֶת בְּנֵיהֶם וְאֶת בְּנֹתֵיהֶם יִשְׂרְפוּ בָאֵשׁ לֵאלֹהֵיהֶם.

Deut 12:29 When YHWH your God cuts off before you the nations which you are coming there to dispossess… 12:30 …and lest you seek out their gods, saying, “How do these nations worship their gods?’ Let me, too, do thus.” 12:31 You shall not do thus for YHWH your God, for every abhorrence of YHWH that He hates they have done for their gods. For even their sons and their daughters they burn in fire to their gods.”

While Deuteronomy presents the practice as Canaanite in origin, elsewhere in the Bible we are told Judahites make these offerings.

Judahite Child Sacrifice

King Ahaz of Judah is said to have passed his son through the fire:

מלכים ב טז:א בִּשְׁנַת שְׁבַע עֶשְׂרֵה שָׁנָה לְפֶקַח בֶּן רְמַלְיָהוּ מָלַךְ אָחָז בֶּן יוֹתָם מֶלֶךְ יְהוּדָה... טז:ג וַיֵּלֶךְ בְּדֶרֶךְ מַלְכֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וְגַם אֶת בְּנוֹ הֶעֱבִיר בָּאֵשׁ כְּתֹעֲבוֹת הַגּוֹיִם אֲשֶׁר הוֹרִישׁ יְ־הוָה אֹתָם מִפְּנֵי בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל.

2 Kgs 16:1 In the seventeenth year of Pekah son of Remaliah, Ahaz son of Jothan became king, king of Judah… 16:3 And he went the way of the kings of Israel, and even his son he passed through the fire like the abominations of the nations that YHWH had dispossessed before the Israelites.

The same is true of King Manasseh:

מלכים ב כא:א בֶּן שְׁתֵּים עֶשְׂרֵה שָׁנָה מְנַשֶּׁה בְמָלְכוֹ... כא:ב וַיַּעַשׂ הָרַע בְּעֵינֵי יְ־הוָה כְּתוֹעֲבֹת הַגּוֹיִם אֲשֶׁר הוֹרִישׁ יְ־הוָה מִפְּנֵי בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל.... כא:ו וְהֶעֱבִיר אֶת בְּנוֹ בָּאֵשׁ...

2 Kgs 21:1 Twelve years old was Manasseh when he became king… 21:2 And he did what was evil in the eyes of YHWH, like the abominations of the nations that YHWH had dispossessed before the Israelites… 21:6 And he passed his son through the fire…[4]

Ezekiel chastises the people of Judah for sacrificing their children, which he describes as a symbolic feeding of “the foul things,” a pejorative term for idols or foreign gods:

יחזקאל כג:לז כִּי נִאֵפוּ וְדָם בִּידֵיהֶן וְאֶת גִּלּוּלֵיהֶן נִאֵפוּ וְגַם אֶת בְּנֵיהֶן אֲשֶׁר יָלְדוּ לִי הֶעֱבִירוּ לָהֶם לְאָכְלָה... כג:לט וּבְשַׁחֲטָם אֶת בְּנֵיהֶם לְגִלּוּלֵיהֶם וַיָּבֹאוּ אֶל מִקְדָּשִׁי בַּיּוֹם הַהוּא לְחַלְּלוֹ וְהִנֵּה כֹה עָשׂוּ בְּתוֹךְ בֵּיתִי.

Ezek 23:37 For they committed adultery, and there is blood on their hands, and they committed adultery with their foul things, and also their sons whom they before for Me they gave over to be consumed… 23:39 And they slaughtered their children to their foul things and came into My sanctuary on that day to profane it and look, so did they do within my house.[5]

In a different passage in Ezekiel, however, the prophet quotes YHWH, wondering if the deity gave them bad laws:

יחזקאל כ:כד יַעַן מִשְׁפָּטַי לֹא עָשׂוּ וְחֻקּוֹתַי מָאָסוּ וְאֶת שַׁבְּתוֹתַי חִלֵּלוּ וְאַחֲרֵי גִּלּוּלֵי אֲבוֹתָם הָיוּ עֵינֵיהֶם. כ:כה וְגַם אֲנִי נָתַתִּי לָהֶם חֻקִּים לֹא טוֹבִים וּמִשְׁפָּטִים לֹא יִחְיוּ בָּהֶם. כ:כו וָאֲטַמֵּא אוֹתָם בְּמַתְּנוֹתָם בְּהַעֲבִיר כָּל פֶּטֶר רָחַם לְמַעַן אֲשִׁמֵּם לְמַעַן אֲשֶׁר יֵדְעוּ אֲשֶׁר אֲנִי יְ־הוָה.

Ezek 20:24 Inasmuch as they did not do My laws and they spurned My statutes and they profaned My sabbaths and their eyes went after the foul things of their fathers. 20:25 And I on My part gave them statutes that were not good and laws through which they would not live. 20:26 And I defiled them with their gifts when they passed every womb-breach in sacrifice, so that I might desolate them, so they might know that I am YHWH.

As many scholars have noted, this likely refers to the law in the Covenant Collection that states:

שמות כב:כח מְלֵאָתְךָ וְדִמְעֲךָ לֹא תְאַחֵר בְּכוֹר בָּנֶיךָ תִּתֶּן לִּי. כב:כט כֵּן תַּעֲשֶׂה לְשֹׁרְךָ לְצֹאנֶךָ שִׁבְעַת יָמִים יִהְיֶה עִם אִמּוֹ בַּיּוֹם הַשְּׁמִינִי תִּתְּנוֹ לִי.

Exod 22:28 The first yield of your vats and the first yield of your grain you shall not delay to give. The firstborn of your sons you shall give to Me. 22:29 Thus you shall do with your ox and your sheep: seven days it shall be with its mother; on the eight day you shall give it to Me.

While all other biblical law collections require financial redemption (pidyon) of the first born, some scholars take the Covenant Collection at face value, as a requirement for child sacrifice.[6]

Jeremiah and the Tophet of Baʿal

Jeremiah too decries the Judahite practice of child sacrifice, and describes a place called the Tophet, located in the valley of Ben Hinnom on the outskirts of Jerusalem, where these offerings were carried out:

ירמיה ז:לא וּבָנוּ בָּמוֹת הַתֹּפֶת אֲשֶׁר בְּגֵיא בֶן הִנֹּם לִשְׂרֹף אֶת בְּנֵיהֶם וְאֶת בְּנֹתֵיהֶם בָּאֵשׁ אֲשֶׁר לֹא צִוִּיתִי וְלֹא עָלְתָה עַל לִבִּי. ז:לב לָכֵן הִנֵּה יָמִים בָּאִים נְאֻם יְ־הוָה וְלֹא יֵאָמֵר עוֹד הַתֹּפֶת וְגֵיא בֶן הִנֹּם כִּי אִם גֵּיא הַהֲרֵגָה וְקָבְרוּ בְתֹפֶת מֵאֵין מָקוֹם.

Jer 7:31 And they built the high places of the Tophet, which are in the Valley of Ben-Hinnom, to burn their sons and their daughters in fire, that I never charged them and what never came to my mind. 7:32 Therefore, look, a time is coming said YHWH, when “Tophet” shall no longer be said nor “Valley of Ben-Hinnom,” but “Valley of Killing,” and they shall bury in Topheth until there is no room.[7]

Unlike Ezekiel, Jeremiah claims that YHWH never commanded the Israelites to sacrifice their children. Later, Jeremiah explicitly connects the practice to worship of Baʿal, the head of the Canaanite pantheon:

ירמיה יט:ד יַעַן אֲשֶׁר עֲזָבֻנִי וַיְנַכְּרוּ אֶת הַמָּקוֹם הַזֶּה וַיְקַטְּרוּ בוֹ לֵאלֹהִים אֲחֵרִים אֲשֶׁר לֹא יְדָעוּם הֵמָּה וַאֲבוֹתֵיהֶם וּמַלְכֵי יְהוּדָה וּמָלְאוּ אֶת הַמָּקוֹם הַזֶּה דַּם נְקִיִּם. יט:ה וּבָנוּ אֶת בָּמוֹת הַבַּעַל לִשְׂרֹף אֶת בְּנֵיהֶם בָּאֵשׁ עֹלוֹת לַבָּעַל אֲשֶׁר לֹא צִוִּיתִי וְלֹא דִבַּרְתִּי וְלֹא עָלְתָה עַל לִבִּי.

Jer 19:4 Inasmuch as they have forsaken Me and made this place foreign and burned incense in it to other gods which neither they nor their ancestors nor the kings of Judah knew, and they have filled this place with the blood of the innocent. 19:5 And they have built high places to Baʿal, which I did not charge and of which I did not speak and which never came to My mind.

In sum, according to Jeremiah, Judahites sacrificed babies to Baʿal—a Canaanite deity—in a place just outside Jerusalem known as the Tophet. It is possible that the idea of Baʿal consuming the sacrificed babies (Ezek 23:37) reflects a myth, like that of Saturn, of Baʿal consuming his children.[8]

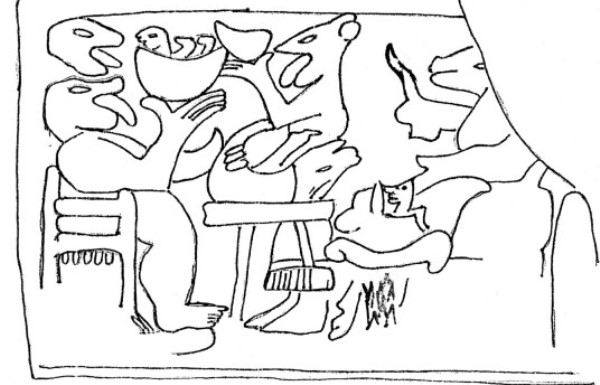

Feeding the god: Seated on the left, a god holds a baby in a bowl in his right hand. In his left hand, he holds a piglet lying on its back on a table. On the bottom right, another baby is being cooked over a fire. From an elaborate tomb in Pozo Moro, Spain, 6th cent. B.C.E.

The Archaeology of Tophets

So far, no archaeological discovery has been found in the in the Ben Hinnom valley, the land of Israel in general, or in the surrounding areas that points to human sacrifices. Nevertheless, extensive evidence of child sacrifice has been found in the western colonies of Phoenicia.

“Phoenician” is not an indigenous term but a name given to the inhabitants of the Canaanite coastal city-states—Tyre, Sidon, Byblos, etc.—by the Greeks. Phoenicians belonged to the Canaanite cultural sphere in all ways, including religion and language.

The Canaanites who lived in these coastal city-states, especially Tyre, were powerful sailors, who established colonies on the Mediterranean shores. The most famous such colony was Carthage (קרת חדשת; compare Hebrew קריה חדשה) “New City,” that later became a superpower.[9] Carthage was culturally Phoenician/Canaanite; they even used a Canaanite dialect (Punic)[10] related to Hebrew written in the 22-letter right-to-left alphabet, which they brought from their motherland.

Eight of these Punic colonies established in today Tunisia, Sicily, and Sardinia contain burial grounds for burnt remains of babies—ashes and charred bones. The children ranged from several days up to one year old, and their ashes were placed in jars used as urns, and buried in the ground. Archaeologists refer to these sites as “[Punic] tophets,” after the biblical name of the specific site or installation in Jerusalem mentioned in the Bible.

All of these “tophets” date to the time the town was established, share the same basic characteristics, and remained active as long as the town existed. Anthropological studies have shown that in all of them the babies were sacrificed in the same manner: they were laid on their backs on a pile of firewood in the open air before the fire was lit.[11]

The most prominent tophet is in Carthage. It was in use from the establishment of the city by Tyrian settlers most likely in the 9th century B.C.E. until the city’s destruction by the Romans in 146 B.C.E. More than 20,000 urns were discovered at the excavated areas. Some of them contain remains of lambs buried in an identical manner. This extraordinary characteristic, found also in other tophets, points to the option some parents apparently had of offering a substitute sacrifice in place of a child.

Notably, the proportion of lambs to human babies over time was descending. In other words, in the bottom, most ancient layer, we find the largest proportion, +/- 30% lambs to babies ration. As we move up on the tell to later periods, the proportion of lambs to humans decreases, so that in the last layer, destroyed by the Romans, we find very few lamb remains. In contrast, after the Romans conquered North Africa, and they prohibited child sacrifices, a new and different type of tophet developed, where only lambs were buried. Scholars call these “neo-Punic tophets.”

Epigraphic Evidence: The m.l.k Sacrifice in Carthaginian Tophets

More than 6,000 inscriptions engraved on stelae were found on the graves of the babies, especially in Carthage.[12] Most of them use a repetitive formula expressing that the burial is the fulfillment of a vow (נדר) that the father (and sometimes the mother) vowed to Baʿal,[13] because Baʿal “heard his/her voice.”

לאדן לבעל חמן אש נדר חנא בן אדנבעל בן גרעשתרת בן אדנבעל כ שמע קלא יברכא

KAI 63 To my lord, to Baʿal-ḤMN. (That) which vowed ḤNʾ son of ʾDN-Baʿal son of GR-ʾAshtoret son of ʾDN-Baʿal because he listened his voice. May he bless him.

לאדן לבעל חמן מתנת אש נדר מגן בן בעלחנא כא שמע קלא ברכה. ים נעם הים ז למגן.

KAI 111 To my lord, to Baʿal-ḤMN. The gift that vowed MGN son of Baʿal-ḤNʾ because he listened his voice (and) blessed him. Today is a good day for MGN.

The word מלך “mlk” appears in many of the inscriptions, as a description of the type of sacrifice, i.e., the offering of a baby.

לאדן לבעל מתנת מתנתא מלך בעל אש נדר עזרבעל בן בעלחנא בן בעליתן אש בעם איתנם.

KAI 99 To my lord, to Baʿal, a gift: The gift of a mlk-bʿl which AZR-Baʿal son of Baʿal-ḤNʾ son of Baʿal-YTN vowed a man from ʾYTNM.

לעדן בעלמן זעבא מילכעתן בן בעליתן במלך ארשם היש ושעמא את קולא[14]

Guelma 19 To my lord, a sacrifice of MYLK-YTN son of Baʿal-YTN of a mlk … and he heard his voice.

לאדן לבעל הקדש בים נעם למלך[15]

To my lord, to the holy Baʿal, on a good day, as a mlk.

Sometimes the term מלכת “mlkt” with the feminine suffix t was used for a female baby. The Canaanite terminology of the stelae is rich, specifying different subtypes of m.l.k sacrifices, such as the mlk-bʿl (meaning uncertain) and the מלכ-אמר mlk-ʾmr, an alternative sacrifice of a lamb instead of a baby.[16]

נצב מלך אמר אש ש[ם אר]ש לבעל [חמן] אדן [כ ש]מע קל דברי

KAI 61b The stele of the mlk-ʾmr that ʾRŠ placed for Baʿal-ḤMN the lord because he listened the voice of his word.

נצב מלך בעל אש שם נחם לבעל חמן אדן כ שמע קל דברי

KAI 61 The stele of the mlk-bʿl that NḤM placed for Baʿal-ḤMN the lord because he listened the voice of his word.

לרבת לתנת פן בעל ולאדן לבעל חמן אש נדר ארשת בת בדעשתרת מלך [א]מר

CIS 307 To my mistress, to Tanit the face of Baʿal, and to my lord, Baʿal-ḤMN, that ʾRŠT daughter of BD-ʿAshtoret vowed, a mlk-ʾmr.

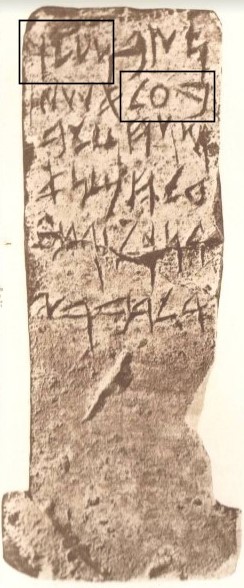

KAI 61: Stela for burial of a burnt baby sacrificed as a molekh; squares mark מלכ בעל. |

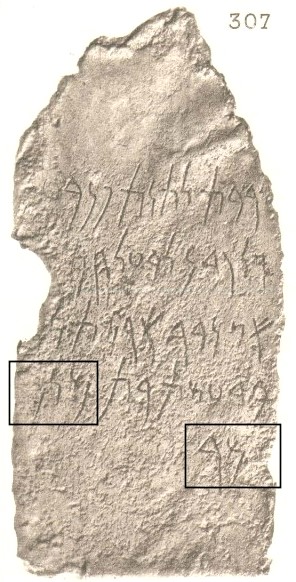

CIS 301: Stela for burial of a burnt lamb sacrificed as a molekh replacement for a baby; squares mark מלכ אמר. |

A Molekh Sacrifice

The term m.l.k appears several times in the Bible in this same context. A final passage comprising Jeremiah’s polemic about the Tophet, in addition to mentioning Baʿal, states that the offerings are la-molekh:

ירמיה לב:לה וַיִּבְנוּ אֶת בָּמוֹת הַבַּעַל אֲשֶׁר בְּגֵיא בֶן הִנֹּם לְהַעֲבִיר אֶת בְּנֵיהֶם וְאֶת בְּנוֹתֵיהֶם לַמֹּלֶךְ אֲשֶׁר לֹא צִוִּיתִים וְלֹא עָלְתָה עַל לִבִּי לַעֲשׂוֹת הַתּוֹעֵבָה הַזֹּאת...

Jer 32:35 And they built high places for Baʿal which are in the Valley of Ben-Hinnom to consign their sons and their daughters la-molekh, which I did not charge them and which never came to My mind to do this abomination….

The phrase la-molekh also appears in Leviticus in the prohibition against sacrificing children:

ויקרא יח:כא וּמִזַּרְעֲךָ לֹא תִתֵּן לְהַעֲבִיר לַמֹּלֶךְ וְלֹא תְחַלֵּל אֶת שֵׁם אֱלֹהֶיךָ אֲנִי יְ־הוָה.

Lev 18:21 And you shall not dedicate any of your see to pass over la-molekh, and you shall not profane the name of your God. I am YHWH.

This is repeated in a more extensive passage:

ויקרא כ:ב ...אִישׁ אִישׁ מִבְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וּמִן הַגֵּר הַגָּר בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל אֲשֶׁר יִתֵּן מִזַּרְעוֹ לַמֹּלֶךְ מוֹת יוּמָת עַם הָאָרֶץ יִרְגְּמֻהוּ בָאָבֶן. כ:ג וַאֲנִי אֶתֵּן אֶת פָּנַי בָּאִישׁ הַהוּא וְהִכְרַתִּי אֹתוֹ מִקֶּרֶב עַמּוֹ כִּי מִזַּרְעוֹ נָתַן לַמֹּלֶךְ לְמַעַן טַמֵּא אֶת מִקְדָּשִׁי וּלְחַלֵּל אֶת שֵׁם קָדְשִׁי.

Lev 20:2 …Every man of the Israelites and of the sojourners who sojourn in Israel who gives of his seed la-molekh is doomed to die. The people of the land shall stone him. 20:3 And as for Me, I shall set My face against that man and cut him off form the midst of his people, for he has given of his seed la-molekh so as to defile my sanctuary and to profane My sacred name.[17]

The classic understanding of ancient and modern commentators alike is that molekh here refers to a god. R. Abraham Ibn Ezra (1089–1164) tries to identify this god with the similarly named Ammonite deity:

אבן עזרא ויקרא יח:כא "למלך" – שם צלם. ודרשו קדמונינו ז"ל שהוא שם כלל, כל מי שימליכנו עליו (בבלי סנהדרין סד.). ויתכן שהוא תועבת בני עמון (מלכים א יא:ה).

Ibn Ezra Lev 18:21 “La-molekh”—the name of an idol. Our predecessors interpreted midrashically that it is a general name, any deity that one enthrones (yamlikh) over oneself (b. San 64a). But it seems likely (or “possible”) that it is a reference to the abomination (i.e., god) of the Ammonites.

Ibn Ezra here is pointing to the Ammonite god Milkom:

מלכים א יא:ה וַיֵּלֶךְ שְׁלֹמֹה אַחֲרֵי עַשְׁתֹּרֶת אֱלֹהֵי צִדֹנִים וְאַחֲרֵי מִלְכֹּם שִׁקֻּץ עַמֹּנִים.

1 Kgs 11:5 And Solomon went after Ashtoreth goddess of the Sidonians and after Milkom abomination of the Ammonites.

One of the most difficult obstacles facing the interpretation of molekh as the name of a deity is the article "the" attached to it, since in Hebrew and all West Semitic languages the names of people, deities, towns, and cities are always anarthrous,[18] while molekh comes clearly definite in la-molekh (לַמֹּלֶךְ) and ha-molekh (הַמֹּלֶך) in Lev 20:5.

The reading of molekh as the name of a god understands the preposition la- in “passing one’s child la-molekh (לַמֹּלֶךְ)” as “to” i.e., giving the child to the god Molekh, so named because he is the king or the ruler. In sacrificial law, however, the preposition le- often introduces the type of sacrifice. For example, the guilt offering law reads:

ויקרא ה:ז וְאִם לֹא תַגִּיע יָדוֹ דֵּי שֶׂה וְהֵבִיא אֶת אֲשָׁמוֹ אֲשֶׁר חָטָא שְׁתֵּי תֹרִים אוֹ שְׁנֵי בְנֵי יוֹנָה לַיהוָה אֶחָד לְחַטָּאת וְאֶחָד לְעֹלָה.

Lev 5:7 And if his hand cannot attain as much as a sheep, he shall bring as his guilt offering for what he has committed two turtledoves or to young pigeons to YHWH, one as an offense offering and one as a burnt offering.

Here, the preposition le- functions not as “to” but as “as” or “for.” If we apply this usage to the molekh verses, the phrase would mean that the child is being offered “as a molekh offering.” This interpretation fits with the usage in the epigraphic finds in the tophets of Carthage in which mlk offerings were explicitly offered to a god named Baʿal or Baʿal-ḤMN. Thus, it is likely that the biblical prohibition to pass a child through fire la-molekh refers to a practice of offering babies, i.e, this is called a molekh sacrifice.

As part of his religious reform, King Manasseh’s son Josiah is said to have destroyed the Tophet near Jerusalem to put an end to molekh offerings:

מלכים ב כג:י וְטִמֵּא אֶת הַתֹּפֶת אֲשֶׁר בְּגֵי (בני) [בֶן] הִנֹּם לְבִלְתִּי לְהַעֲבִיר אִישׁ אֶת בְּנוֹ וְאֶת בִּתּוֹ בָּאֵשׁ לַמֹּלֶךְ.

2 Kgs 23:10 And he defiled the Topheth that was in the Valley of Hinnom, so that no man would pass his son or his daughter through the fire as a molekh offering.

If this claim is historical, it would mean that the Josianic reform is the time when the polemic we see expressed in Deuteronomy and Jeremiah and Ezekiel came to an end.[19]

The Binding of Isaac

A more subtle example of a polemic against the child sacrifice comes from the Akedah, the story of the binding of Isaac,[20] whose central message is that the God of Israel demands Israelites be ready to sacrifice their sons, but by no means to actually do it.

This interpretation of the Akedah is conveyed through the terminology it uses:

יְחִיד “only”?—Isaac is called “the yechid” of Abraham (Genesis 22:2, 12, 16), generally translated as the “unique” or “only” son of Abraham.[21] But in biblical Hebrew, the word for this would be אחד, also the standard term for “one.”[22] The word יְחִיד or its feminine form יְחִידָה is rare in Biblical Hebrew, and it is used almost exclusively for children intended to be sacrificed by their fathers like Isaac in this story or the Jephthah’s daughter (Judges 11:34). The identical term is used in the Canaanite mythology for a son intended to be sacrificed, as attested by Eusebius of Caesarea quoting the Phoenician priest Sanchuniathon:

Eusebius, Praeparatio Evangelica I.10.44/IV.16.6 It was a custom of the ancients in great crises of danger for the rulers of a city or nation, in order to avert the common ruin, to give up the most beloved of their children for sacrifice as a ransom to the avenging daemons; and those who were thus given up were sacrificed with mystic rites. Kronos (=Baʿal) then, whom the Phoenicians call (in Phoenician) el (אל = god), who was king of the country and subsequently, after his decease, was deified as the star Saturn, had by a nymph of the country named Anobret an only begotten son, whom they on this account called (in Phoenician) yeud (יחוד/יחיד), the only begotten being still so called among the Phoenicians; and when very great dangers from war had beset the country, he arrayed his son in royal apparel, and prepared an altar, and sacrificed him.

On the wood—As noted above, m.l.k sacrifices were laid on their backs on a pile of firewood in the open air before the fire was lit. This is what the story describes Abraham doing to Isaac:

בראשית כב:ט וַיָּבֹאוּ אֶל הַמָּקוֹם אֲשֶׁר אָמַר לוֹ הָאֱלֹהִים וַיִּבֶן שָׁם אַבְרָהָם אֶת הַמִּזְבֵּחַ וַיַּעֲרֹךְ אֶת הָעֵצִים וַיַּעֲקֹד אֶת יִצְחָק בְּנוֹ וַיָּשֶׂם אֹתוֹ עַל הַמִּזְבֵּחַ מִמַּעַל לָעֵצִים.

Gen 22:9 And they came to the place that God had said to him, and Abraham built there an altar and laid out the wood and bound Isaac his son and placed him on the altar on top of the wood.

In contrast, animal sacrifices are killed first and placed in pieces on the wood.

Ram or lamb?—Early in the story, Isaac asks Abraham about the absence of the שֶׂה (śe), the lamb:

בראשית כב:ז וַיֹּאמֶר יִצְחָק אֶל אַבְרָהָם אָבִיו וַיֹּאמֶר אָבִי וַיֹּאמֶר הִנֶּנִּי בְנִי וַיֹּאמֶר הִנֵּה הָאֵשׁ וְהָעֵצִים וְאַיֵּה הַשֶּׂה לְעֹלָה. כב:ח וַיֹּאמֶר אַבְרָהָם אֱלֹהִים יִרְאֶה לּוֹ הַשֶּׂה לְעֹלָה בְּנִי וַיֵּלְכוּ שְׁנֵיהֶם יַחְדָּו.

Gen 22:7 And Isaac said to Abraham his father: “Father!” and he said, “Here I am, my son.” And he said, “Here is the fire and the wood but where is the lamb for the offering?” 22:7 And Abraham said, “God will see to the lamb my son.” And the two of them went together.

After the messenger stops Abraham from sacrificing Isaac, Abraham discovers not a שֶׂה but an אַיִל (ʾayil), a ram.

בראשית כב:יג וַיִּשָּׂא אַבְרָהָם אֶת עֵינָיו וַיַּרְא וְהִנֵּה אַיִל אַחַר [תה"ש נ"ש: אחד] נֶאֱחַז בַּסְּבַךְ בְּקַרְנָיו וַיֵּלֶךְ אַבְרָהָם וַיִּקַּח אֶת הָאַיִל וַיַּעֲלֵהוּ לְעֹלָה תַּחַת בְּנוֹ.

Gen 22:13 And Abraham raised his eyes and saw and, look, a ram was caught in the thicket by its horns, and Abraham went and took the ram and offered him up as a burnt offering instead of his son.

As discussed above, lambs were the typical alternative used instead of babies in Carthage, the מלכ-אמר subtype. A lamb is an appropriate substitute for a baby, but an inappropriate one for a mature boy such as Isaac, for whom a ram was a more appropriate alternative.

But, in the end, God prefers an appropriate substitute to the real thing; Abraham is stopped from bringing a molekh. The Akedah wishes to teach that what was a marginal alternative in the Canaanite culture, was by contrast the only desirable such sacrifice in the Israelite cult.[23]

Addendum

Other Types of Human Sacrifice in the Bible

In addition to the molekh sacrifice of babies, the Bible refers to other types of human sacrifice.

To Save a City

In the story in which Israel, Judah, and Edom lay siege to Moab, King Mesha offers his son as a sacrifice, ostensibly to his own god Kemosh, as a last resort to save the city from destruction:

מלכים ב ג:כו וַיַּרְא מֶלֶךְ מוֹאָב כִּי חָזַק מִמֶּנּוּ הַמִּלְחָמָה וַיִּקַּח אוֹתוֹ שְׁבַע מֵאוֹת אִישׁ שֹׁלֵף חֶרֶב לְהַבְקִיעַ אֶל מֶלֶךְ אֱדוֹם וְלֹא יָכֹלוּ. ג:כז וַיִּקַּח אֶת בְּנוֹ הַבְּכוֹר אֲשֶׁר יִמְלֹךְ תַּחְתָּיו וַיַּעֲלֵהוּ עֹלָה עַל הַחֹמָה וַיְהִי קֶצֶף גָּדוֹל עַל יִשְׂרָאֵל וַיִּסְעוּ מֵעָלָיו וַיָּשֻׁבוּ לָאָרֶץ.

2 Kgs 3:26 And the king of Moab saw that the battle was hard against him, and he took seven hundred sword-wielding men with him to break through to the king of Edom, but they were not able. 3:27 And he took his firstborn son, who would have been king after him, and offered him up as a burnt offering on the wall, and a great fury came against Israel, and they journeyed away from him and went back to the land.[24]

The story suggests that the sacrifice was effective: the besieging army retreat. This type of human sacrifice is known from epigraphic sources from the ANE.

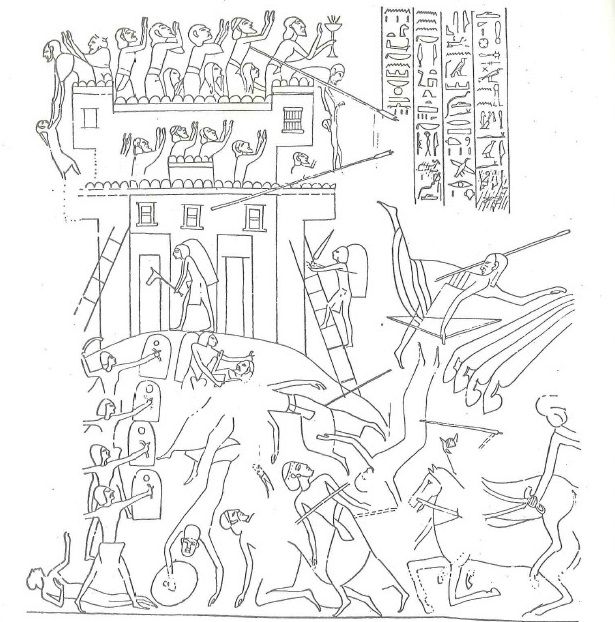

Seven Egyptian reliefs dated to the 13th–12th centuries B.C.E. depict Canaanite cities besieged by the Egyptian army. On the walls of the city, a child—most probably a son of the king—is being offered as a sacrifice by the local priests. One relief, depicting the city of Ashkelon, contains a caption explaining that the deity addressed is Baʿal.[25]

Pharaoh Merneptah’s siege of the Canaanite city of Ashkelon. On the tower on the right, a priest holds a chalice while a man drops the dead body of a child (note the diminutive size and the hairlock), ostensibly the king’s son, over the side of the wall. A little girl is being dropped off the tower on the left, while the people raise their hands in prayer to Baʿal, hoping in vain to be saved from the siege. Below, Egyptian soldiers attack.

Pharaoh Merneptah’s siege of the Canaanite city of Ashkelon. On the tower on the right, a priest holds a chalice while a man drops the dead body of a child (note the diminutive size and the hairlock), ostensibly the king’s son, over the side of the wall. A little girl is being dropped off the tower on the left, while the people raise their hands in prayer to Baʿal, hoping in vain to be saved from the siege. Below, Egyptian soldiers attack.

About thirty classical (Greek and Latin)[26] sources speaking about Punic cities, and in one case the Phoenician city of Tyre, describe the sacrifice of the son or sons of the leaders of the city to Baʿal (named as Kronos or Saturn) for the salvation of the city of a siege or a plague. The historian Quintus Curtius Rufus tells of the famous siege of Tyre by Alexander the Great in 332 B.C.E., and quotes the authorities of the desperate besieged city:

Rufus Book IV 3:23 Some even proposed renewing a sacrifice which had been discontinued for many years, and which I for my part should believe to be by no means pleasing to the gods, of offering a freeborn boy to Saturn (=Baʿal). This sacrilege rather than sacrifice, handed down from their founders, the Carthaginians are said to have performed until the destruction of their city, and unless the elders, in accordance to with whose counsel everything was done, had opposed it, the awful superstition would have prevailed over mercy.

The reference to “renewing” the sacrifice shows that they had stopped offering it. This is because, by the time of Alexandar’s conquest, Tyre had already been subject to two centuries of Persian rule, and the Persians had banned the practice, much as Rome did in Carthage when they conquered it.[27]

Fulfillment of a Vow

The Bible also refers to the killing of people as fulfillment of a vow. For example, Leviticus lays out the rule if someone makes a cherem—dedication to God[28]—vow about someone under their control, ostensibly a slave or a child:

ויקרא כז:כח אַךְ כָּל חֵרֶם אֲשֶׁר יַחֲרִם אִישׁ לַי־הוָה מִכָּל אֲשֶׁר לוֹ מֵאָדָם וּבְהֵמָה וּמִשְּׂדֵה אֲחֻזָּתוֹ לֹא יִמָּכֵר וְלֹא יִגָּאֵל כָּל חֵרֶם קֹדֶשׁ קָדָשִׁים הוּא לַי־הוָה. כז:כט כָּל חֵרֶם אֲשֶׁר יָחֳרַם מִן הָאָדָם לֹא יִפָּדֶה מוֹת יוּמָת.

Lev 27:28 But anything proscribed, that a man may proscribe for YHWH, of anything he has, whether of humans or animals or of the field of his holding, shall not be sold and shall not be redeemed. Anything proscribed is holy of holies to YHWH. 27:29 No human who has been proscribed may be ransomed. He is doomed to die.[29]

Similarly, the book of Judges tells that Jephthah made a vow before going to war against the Ammonites:

שופטים יא:ל וַיִּדַּר יִפְתָּח נֶדֶר לַי־הוָה וַיֹּאמַר אִם נָתוֹן תִּתֵּן אֶת בְּנֵי עַמּוֹן בְּיָדִי. יא:לא וְהָיָה הַיּוֹצֵא אֲשֶׁר יֵצֵא מִדַּלְתֵי בֵיתִי לִקְרָאתִי בְּשׁוּבִי בְשָׁלוֹם מִבְּנֵי עַמּוֹן וְהָיָה לַי־הוָה וְהַעֲלִיתִהוּ עוֹלָה.

Judg 11:30 And Jephthah made a vow to YHWH and said: 11:31 “If you indeed give the Ammonites into my hand, it shall be that whoever comes out of the door of my house to meet me when I return safe and sound from the Ammonites shall be YHWH’s and I shall offer him up as a burnt offering.

Jephthah wins the battle, but the story turns to tragedy when his daughter is the first to receive him home, and so he “fulfilled the vow,” mostly like meaning that he performed the sacrifice as he had vowed.[30]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

May 13, 2024

|

Last Updated

February 10, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Daniel Vainstub is Lecturer in the Department of Bible, Archaeology and Ancient Near East, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, where he did his Ph.D. His dissertation is titled Governmental Institutions in Phoenician Cities from the Bronze Age through the Beginning of the Roman Period. Vainstub is the editor of The Persian and Hellenistic Periods in Israel. A Southern Perspective (Beer Sheva 2018) and Worship and Burial in the Shfela and Negev Regions throughout the Ages (Beer Sheva 2019). His research on the Lachish comb was featured on the BBC and his work on the Ophel inscription was selected as among the top-ten in 2023 by ASOR

Essays on Related Topics: