Edit article

Edit articleSeries

What Sin Caused the Destruction of the First Temple?

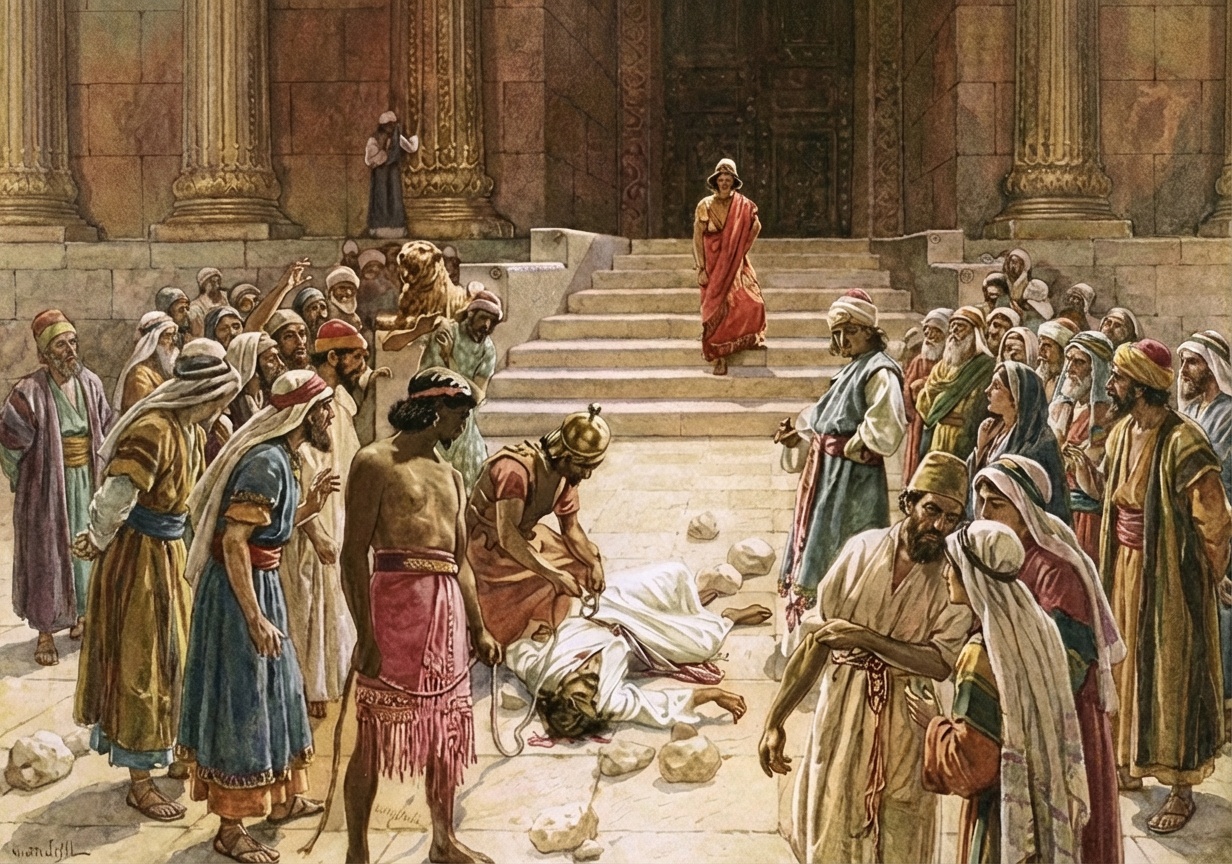

Murder of Zechariah, William Hole (1846–1917). Wikimedia. Adapted with AI.

Why Is the Land in Ruins?

The book of Jeremiah, probably written soon after the destruction of the First Temple, asks the big question: What caused the destruction?

ירמיה ט:יא מִי הָאִישׁ הֶחָכָם וְיָבֵן אֶת זֹאת וַאֲשֶׁר דִּבֶּר פִּי יְ־הוָה אֵלָיו וְיַגִּדָהּ עַל מָה אָבְדָה הָאָרֶץ נִצְּתָה כַמִּדְבָּר מִבְּלִי עֹבֵר.

Jer 9:11 What man is so wise that he understands this? To whom has YHWH’s mouth spoken, so that he can explain it: Why is the land in ruins, laid waste like a wilderness, with none passing through?

God’s answer follows:

ט:יב וַיֹּאמֶר יְ־הוָה עַל עָזְבָם אֶת תּוֹרָתִי אֲשֶׁר נָתַתִּי לִפְנֵיהֶם וְלֹא שָׁמְעוּ בְקוֹלִי וְלֹא הָלְכוּ בָהּ. ט:יג וַיֵּלְכוּ אַחֲרֵי שְׁרִרוּת לִבָּם וְאַחֲרֵי הַבְּעָלִים אֲשֶׁר לִמְּדוּם אֲבוֹתָם.

9:12 YHWH replied: “Because they forsook the Torah I had set before them. They did not obey Me and they did not follow it, 9:13 but followed their own willful heart and followed the Baʿalim, as their fathers had taught them.”

God accuses the Judahites of ignoring his laws and going after the Baʿalim, other gods. Centuries later, rabbinic texts adopted Jeremiah’s answer, but added two more sins (b. Yoma 9b):

מקדש ראשון מפני מה חרב? מפני ג' דברים שהיו בו ע"ז וגלוי עריות ושפיכות דמים.

Why was the first Temple destroyed? For the three [cardinal] sins: idolatry, illicit sexuality, and murder.[1]

In contrast, the poems in the book of Lamentations[2] list no specific sins the Judahites committed:

איכה א:ה ...יְ־הוָה הוֹגָהּ עַל רֹב פְּשָׁעֶיהָ...

Lam 1:5 …YHWH has afflicted her for her many transgressions…

איכה א:ח חֵטְא חָטְאָה יְרוּשָׁלִַם...

Lam 1:8 Jerusalem has sinned…

איכה ד:ו וַיִּגְדַּל עֲוֹן בַּת־עַמִּי מֵחַטַּאת סְדֹם...

Lam 4:6 The guilt of my poor people exceeded the iniquity of Sodom…[3]

The author believes in providence, is certain that the destruction was warranted, and sees it as God’s will, but doesn’t suggest specifics.

The Killing of a Priest and Prophet

One phrase in Lamentations, however, has been interpreted as describing one specific appalling sin:

איכה ב:כ רְאֵה יְ־הוָה וְהַבִּיטָה לְמִי עוֹלַלְתָּ כֹּה אִם תֹּאכַלְנָה נָשִׁים פִּרְיָם עֹלֲלֵי טִפֻּחִים אִם יֵהָרֵג בְּמִקְדַּשׁ אֲדֹנָי כֹּהֵן וְנָבִיא.

Lam 2:20 See, O YHWH, and behold, to whom You have done this! If women eat their own fruit, their new-born babes! If priest and prophet were slain in the Sanctuary of the Lord!

The use of the passive here, “יֵהָרֵג—was/were slain”[4] leaves the guilty party ambiguous. The ambiguous usage of this line in a qinah (a poem of lament) recited on Tisha be’Av highlights several possible interpretations.

The Qinah אם תאכלנה

Elazar (ha-)Qalir(i), the great liturgical poet,[5] composed a qinah recited during the morning service,[6] titled אם תאכלנה, “If [women] eat”—the phrase immediately preceding the reference to the priest and prophet. Structurally, the qinah follows the acrostic pattern of Lamentations 1–4—twenty-two poetic lines corresponding to the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet. Mostly, Qalir simply bewails the destruction. The first three lines of the qinah, for example, read:

אִם תֺּאכַלְנָה נָשִׁים פִּרְיָם עוֹלְלֵי טִפּוּחִים, אַלְלַי לִי:

When (I think how) women could devour their own offspring, the children of their tender care (Lam 2:20), Woe is me!

אִם תְּבַשֵּׁלְנָה נָשִׁים רַחֲמָנִיּוֹת יַלְדֵיהֶן הַמְּדוּדִים טְפָחִים טְפָחִים, אַלְלַי לִי:

When (I think how) compassionate women could boil their own children who were so carefully nurtured (Lam 4:10), Woe is me!

אִם תִּגּוֹזְנָה פְּאַת רֺאשָׁם וְתִקָּשַׁרְנָה לְסוּסִים פּוֹרְחִים, אַלְלַי לִי:

When (I think how) the tresses of their heads could be cut off and tied (as adornment) upon the enemy’s fleet horses, Woe is me![7]

After these 22 lines of lament, Qalir imagines God retorting with a critique that includes the line about the priest and prophet. This line’s meaning, however, is opaque.[8] God’s critique refers to שְׁכֵנַי הָרָעִים—literally, “my evil neighbors,” a term that could refer to the Judahites themselves or to the countries neighboring Judah—especially Edom (e.g. Ps 137:7)—or even the Babylonians, who invaded and destroyed Judah. The difference in meaning leads to wildly different understandings of who killed the priests and prophets.[9]

Comparing two different translations highlights the difficulty of this line:

Qalir |

Weinreb trans. |

Rosenfeld trans. |

|

וְרוּחַ הַקֺּדֶשׁ לְמוּלָם מַרְעִים |

The Holy Spirit thunders against them: |

The Holy One thunders (His anger, exclaiming): |

|

הוֹי עַל כָּל שְׁכֵנַי הָרָעִים. |

Woe to the wicked of the Jewish people! |

“Woe to all my bad neighbours.” |

|

מַה שֶּׁהִקְרָאָם מוֹדִיעִים. |

They inform others about what has befallen them |

They announce the fate which they brought (upon Israel) |

|

וְאֵת אֲשֶׁר עָשׂוּ לֹא מוֹדִיעִים. |

But do not inform others about what they have done. |

But what they themselves committed they do not announce. |

|

"אִם תֺּאכַלְנָה נָשִׁים פִּרְיָם" מַשְׁמִיעִים. |

They give voice to the fact that women eat their own children, |

When women are forced to eat their own offspring they proclaim (the scandal), |

|

"וְאִם יֵהָרֵג בְּמִקְדַּשׁ יְיָ כֺּהֵן וְנָבִיא" לֹא מַשְׁמִיעִים: |

But to the fact that they killed a prophet and a priest in the Temple, they do not give voice. |

But when they themselves slay a priest and a prophet in the Sanctuary of the Lord, they do not publish it. |

Rabbi Tzvi Hersh Weinreb in The Koren Mesorat HaRav Kinot, reads it to mean that God has interrupted the words of the lamenting poet to explain what terrible sin of the Jews led to the destruction.[10] In contrast, Rabbi Abraham Rosenfeld in the Tisha B’av Compendium understands it as a response to the Judahites’ gloating neighbors, reminding them of their crimes.

Qalir may be ambiguous, but classical rabbinic sources are clear in understanding the verse as a reference to an Israelite sin.

The Bubbling Blood of the Prophet Zechariah: Talmud Bavli

In a Talmudic passage often studied on Tisha be’Av,[11] the rabbis describe the destruction of the First Temple by the Babylonians (b. Gittin 57b):

אמר רבי יהושע בן קרחה: סח לי זקן אחד מאנשי ירושלים, בבקעה זו הרג נבוזראדן רב טבחים מאתים ואחת עשרה רבוא עד שהלך דמן ונגע בדמו של זכריה לקיים מה שנאמר ודמים בדמים נגעו

Rabbi Yehoshua ben Korḥah said: An old man from among the inhabitants of Jerusalem related to me: In this valley [that lies before you], Nebuzaradan, captain of the guard [of the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar], killed 2,110,000 Jews, until their flowing blood came in contact with the blood of Zechariah, to fulfill what [the prophet] said (Hos 4:2): “And blood came into contact with blood.”

אשכחיה לדמיה דזכריה דהוה קא מרתח וסליק אמר מאי האי אמרו ליה דם זבחים דאשתפוך אייתי דמי ולא אידמו אמר להו אי אמריתו לי מוטב ואי לאו מסריקנא לבשרייכו במסרקי דפרזלי

[Nebuzaradan] saw that that the blood of Zechariah was bubbling up. He said: “What is this?” They said to him: “It is the blood spilled from sacrifices.” He brought [animal] blood and it did not look the same. He said to them: “If you tell me the truth, it will be well with you. If not, I will rake your flesh with iron rakes.”

אמרי ליה: מאי נימא לך, נבייא הוה בן דהוה קא מוכח לן במילי דשמיא, קמינן עילויה וקטלינן ליה, והא כמה שנין דלא קא נייח דמיה.

They said to him: “What shall we say to you? He was a prophet among us, who used to rebuke us about religious matters, and we rose up against him, and killed him, and for many years now his blood has not settled.”

The murdered prophet Zechariah mentioned in the Talmud appears in a story in Chronicles. During the reign of King Joash, after the death of the righteous high priest, Jehoiada, the people began to sin, prompting God to send a prophetic warning through Jehoiada’s son, Zechariah:

דברי הימים ב כד:כ וְרוּחַ אֱלֹהִים לָבְשָׁה אֶת זְכַרְיָה בֶּן יְהוֹיָדָע הַכֹּהֵן וַיַּעֲמֹד מֵעַל לָעָם וַיֹּאמֶר לָהֶם כֹּה אָמַר הָאֱלֹהִים לָמָה אַתֶּם עֹבְרִים אֶת מִצְוֹת יְ־הוָה וְלֹא תַצְלִיחוּ כִּי עֲזַבְתֶּם אֶת יְ־הוָה וַיַּעֲזֹב אֶתְכֶם. כד:כא וַיִּקְשְׁרוּ עָלָיו וַיִּרְגְּמֻהוּ אֶבֶן בְּמִצְוַת הַמֶּלֶךְ בַּחֲצַר בֵּית יְ־הוָה.

2 Chr 24:20 Then the spirit of God enveloped Zechariah son of Jehoiada the priest; he stood above the people and said to them, “Thus God said: Why do you transgress the commandments of YHWH when you cannot succeed? Since you have forsaken YHWH, He has forsaken you.” 24:21 They conspired against him and pelted him with stones in the court of the House of YHWH, by order of the king.

Reading the words in Lamentations 2:20 as referring to the story of Zechariah, the Talmud understands the vav, “and,” that separates the nouns כֹּהֵן וְנָבִיא, to indicate not two individuals, but a single person who was both a priest and a prophet.[12] Notably, Avigdor Shinan of Hebrew University hesitatingly suggests the opposite etiology: that the author of Chronicles had our verse in Lamentations in mind, and wrote the story of Zechariah as a kind of expansive derashah (exposition) on it.[13]

As he dies, Zechariah prophesies that God will take vengeance:

דברי הימים ב כד:כב וְלֹא זָכַר יוֹאָשׁ הַמֶּלֶךְ הַחֶסֶד אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה יְהוֹיָדָע אָבִיו עִמּוֹ וַיַּהֲרֹג אֶת בְּנוֹ וּכְמוֹתוֹ אָמַר יֵרֶא יְ־הוָה וְיִדְרֹשׁ.

2 Chr 24:22 King Joash had no regard for the loyalty that his father Jehoiada had shown to him, and killed his son. As he was dying, he said, “May YHWH see and requite it.”

Given the centuries-long gap between the murder of Zechariah, in the time of King Joash, and the destruction of the Temple in 586 B.C.E., the Talmud is envisioning the blood of this murdered priest-prophet as having bubbled for over 200 years.[14] (In Jerusalem today one can find the alleged grave of Zechariah, designated “The prophet’s revenge.”[15])

In the New Testament, Matthew (23:31–35) quotes Jesus as chastising the scribes and the Pharisees, telling them that “You testify against yourselves that you are the descendants of those who murdered the prophets,” promising that “upon you may come [punishment for] all the righteous blood shed on earth, from the blood of righteous Abel to the blood of Zechariah son of Barachiah,[16] whom you murdered between the sanctuary and the altar.”[17]

Reading the Verse as a Dialogue

The Talmud’s understanding of the verse requires reading it as a dialogue. After the lamenter says “How could you have done this to us? How could you have reduced us to eating our own children?” God, or God’s representative, answers, “How could you have committed the terrible crime of the murder of Zechariah?” That is how Rashi (1040–1105), who follows the Talmudic interpretation, explains the verse:

רוח הקודש משיבתם: וכי נאה לכם שהרגתם את זכריה בן יהוידע...והיה כהן ונביא והרגוהו בעזרה

The Holy Spirit [i.e. God] responded to them,[18] “And was it proper for you to kill Zechariah the son of Jehoiada?” …he was a priest and a prophet, and they killed him in the Temple.

As Ed Greenstein of Bar Ilan University notes, in his “Voices in Lamentations: Dialogues in Trauma” (TheTorah 2015), Lamentations is a multivocal text:

[I]t is evident to any reader/hearer that there are several different voices to be discerned in the Scroll. These voices interact, producing a drama, or rather a series of dramas, from within the dialogues of which the text is composed.”

Indeed, Greenstein points out that, at times, the voices in Lamentations interrupt each other within the same verse.[19] According to this Talmudic interpretation cited by Rashi, God would be the one interrupting here, but, as Greenstein writes, the one voice that is conspicuously absent from the book of Lamentations is the voice of God. The author of Lamentations speaks to and about God, but never quotes God.

The Medieval Peshat Explanation

The immediate context offers a stronger argument against reading the phrase as a complaint about Israel’s sin:

איכה ב:כ רְאֵה יְ־הוָה וְהַבִּיטָה לְמִי עוֹלַלְתָּ כֹּה

Lam 2:20 See, O YHWH, and behold, to whom You have done this!

אִם תֹּאכַלְנָה נָשִׁים פִּרְיָם עֹלֲלֵי טִפֻּחִים

If women eat their own fruit, their new-born babes!

אִם יֵהָרֵג בְּמִקְדַּשׁ אֲדֹנָי כֹּהֵן וְנָבִיא.

If priest and prophet were slain in the Sanctuary of the Lord!

The first two clauses of the verse are undeniably a plaintive lament on the reduced fortune of the Jews. It makes sense that the next clause continues in the same direction: “Why, God have You treated us like this? Why did You force us to deteriorate to cannibalism in order to stay alive? Why did You allow the enemy to slay our priests and prophets in the holy Temple?”[20]

Thus, Joseph ibn Kaspi (1278–1340) explains:

אם יהרג—ע״י נבוכדנצר, ואין ספק שנביאים רבים מתו שם, ואם נמלטו ירמיה וברוך, כי היו היותר מעולים

[Priest and prophet] were slain: by Nebuchadnezzar: Doubtless, many prophets died there [in the Temple at the hands of the Babylonians who captured it] even if the best of them [of the prophets], Jeremiah and Baruch, escaped.

In other words, ibn Kaspi says that we do not have to find a specific story of a priest and/or a prophet being killed in the Temple. The Babylonians committed such atrocities, even if we don’t know their victims’ names.[21] These killings were part and parcel of the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem; the verse in Lamentations is not meant to describe sinful activities of Jews killing their own priests and prophets.[22]

Ibn Kaspi here is expanding upon the laconic remark of Abraham ibn Ezra (1092–1167), who, though well-acquainted with the midrashic tradition, dismisses it as not a peshat reading:

והמפרש כי על זכריה ידבר דרך דרש

Anyone who interprets this phrase [“Priest and prophet were slain in the Sanctuary of the Lord”] about Zechariah is offering a midrashic explanation [i.e., not the plain sense of the text].

No Facile Explanations in Lamentations

Thus, Lamentations leaves us without a specific sin to explain what Judah did to deserve this fate. As Yael Ziegler of Herzog College writes, “Glaringly absent [in Lamentations] are an inventory of Israel’s sins, a consistent portrayal of God’s nature, and a clear notion of how to explain the catastrophic events...”[23]

In fact, according to at least one voice in Lamentations, the fate that befell the Israelites in 586 B.C.E. cannot be attributed to any sin that occurred in their days, but to earlier unspecified sins:

איכה ה:ז אֲבֹתֵינוּ חָטְאוּ (אינם) [וְאֵינָם] (אנחנו) [וַאֲנַחְנוּ] עֲוֹנֹתֵיהֶם סָבָלְנוּ.

Lam 5:7 Our fathers sinned and are no more; and we must bear their guilt.[24]

We can understand the desire of the midrashic tradition to find in Lamentations an attempt to explain the tragedy theologically and to discover God’s voice somewhere in the text.[25] At the same time, we can be impressed by the author of Lamentations’ refusal to provide facile explanations, deciding instead to simply mourn the losses experienced by the people:

איכה ג:מב נַחְנוּ פָשַׁעְנוּ וּמָרִינוּ אַתָּה לֹא סָלָחְתָּ.

Lam 3:42 We have transgressed and rebelled, and You have not forgiven

As the scholar Michael S. Moore wrote: “[Lamentations] was primarily designed in order to lament the nation’s destruction, to put forward a first step toward picking up the emotional pieces, to articulate the anger, guilt, despair, and stubborn hopes of a nation,”[26] but not to explain.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

July 31, 2022

|

Last Updated

December 31, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Rabbi Marty Lockshin is Professor Emeritus at York University and lives in Jerusalem. He received his Ph.D. in Near Eastern and Judaic Studies from Brandeis University and his rabbinic ordination in Israel while studying in Yeshivat Merkaz HaRav Kook. Among Lockshin’s publications is his four-volume translation and annotation of Rashbam’s commentary on the Torah.

Essays on Related Topics: